A.E. Waite’s Vision: Two Tarots to Rule Them All

PART ONE: Playing to both the public and the inner circle of his mystery school, one of the occult Tarot's founding fathers gave the world a double dose of beauty

THIS IS THE FIRST PART OF A THREE-PART SERIES ON WOODRUFF.

THERE’S PROBABLY A FORGOTTEN A.E. Waite and Pamela Colman Smith Tarot deck stashed somewhere in your kitchen drawer—still waiting to reveal its secrets during the next full moon.

I carry a miniature version in my car’s glove compartment because you never know when a cop would rather have an impromptu reading than spend time writing up a ticket. (This actually happened to yours truly. Thank goddess the three-card draw’s outcome was the Six of Wands.)

The Waite-Smith Tarot as directed and overseen by the occultist Arthur E. Waite has become the equivalent of the Marvel franchise of the Tarot world—the most popular Tarot deck in the universe.

The deck has deservedly laid claim to Western culture’s love affair with all things fringe or New Age. Colman Smith’s illustrations for the deck are both charming and unsettling—in the way Walt Disney’s Bambi introduced the beauty and terror of nature into our child-mind.

Placed within the matrix of a reshuffle-able trajectory, the magical symbols, and icons that Waite and Colman Smith assembled speak directly to our wish to impress order on the random and chaotic.

Art like this—easily accessible (and carried in a purse or glove compartment)—is worth scores of Xanax prescriptions or expensive therapeutic excursions with a shrink.

A whimsical prototype

During the last century, the Waite-Smith deck became the de facto criterion for all POMO (post-modern) Tarot decks that have followed in its wake. None of which—save for the Aleister Crowley and Lady Frieda Harris Thoth deck—contain much metaphysical gravitas—at least as scholarship relates to a deck’s lineage.

Graphically, there are some genuinely beautiful POMO Tarot decks available—like Robert E. Place’s many recreations and iterations (a vampire Tarot deck anyone?)

But for every beauty, there’s a beast—like the aesthetics-destroying Motherpeace Tarot—a ‘circular’ deck of cards that banished the phallocentric influence (those straight erect edges) and makes for fabulous cocktail coasters.

As someone who was boot camp-instructed in the Tarot—by working consistently with both decks (I must have done over two thousand readings when I worked as a telephone psychic years ago), I’ve found subsequent POMO decks to be charming (or alarming) but lacking in the ineffable magic that Colman Smith and Harris siphoned from the molten brains of their male muses.

Rectification and guidance

For his first attempt at a deck, Arthur E. Waite, a mystic Christian and former member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, formed a friendship with Colman Smith shortly after the young artist was drafted by W. B. Yeats into the Order.

After their group disbanded—a phenomenon that happened like clockwork with secret societies in the early 20th century, Colman followed Waite into the Holy Order of the Golden Dawn. And it was there, in 1909, that Waite commissioned Colman Smith to create what he eventually named ‘the rectified Tarot.’

Rectified because Waite, like other reconstructive visionaries, was certain he had discovered a more accurate application of the Tarot’s innate symbols—a feral hodgepodge of images collected over the years from various iterations of the cards. He especially wished to dispel the false notion that the Tarot was a byproduct of ancient Egyptian mystery schools.

What’s particularly impressive about the Smith-Waite deck is how quickly—and with such overarching perspicacity—Colman Smith was able to create a complete and comprehensive collection of work. She designed all 78 cards in a period of several months (and for very little money).

As an artist myself, that understands the rigors of two-dimensional creation, you must channel an extraordinary force—a kind of guidance if you will—to have your work arrive so finetuned and finished.

In researching this article I came across a fascinating footnote regarding the esoteric underpinnings of the Waite-Smith deck. R. A. Gilbert’s detailed biography, A.E. Waite: Magician of Many Parts tells of Waite intimating that someone who was “deeply versed” in the subject of “The Secret Tradition” assisted Waite and Colman in the deck’s arrangement and choice of symbols.

Waite does not identify the helper, but there’s little doubt to Gilbert that it was W. B. Yeats, who had remained friendly with Waite despite another failing of a secret school they’d both attended.

All the world’s a stage

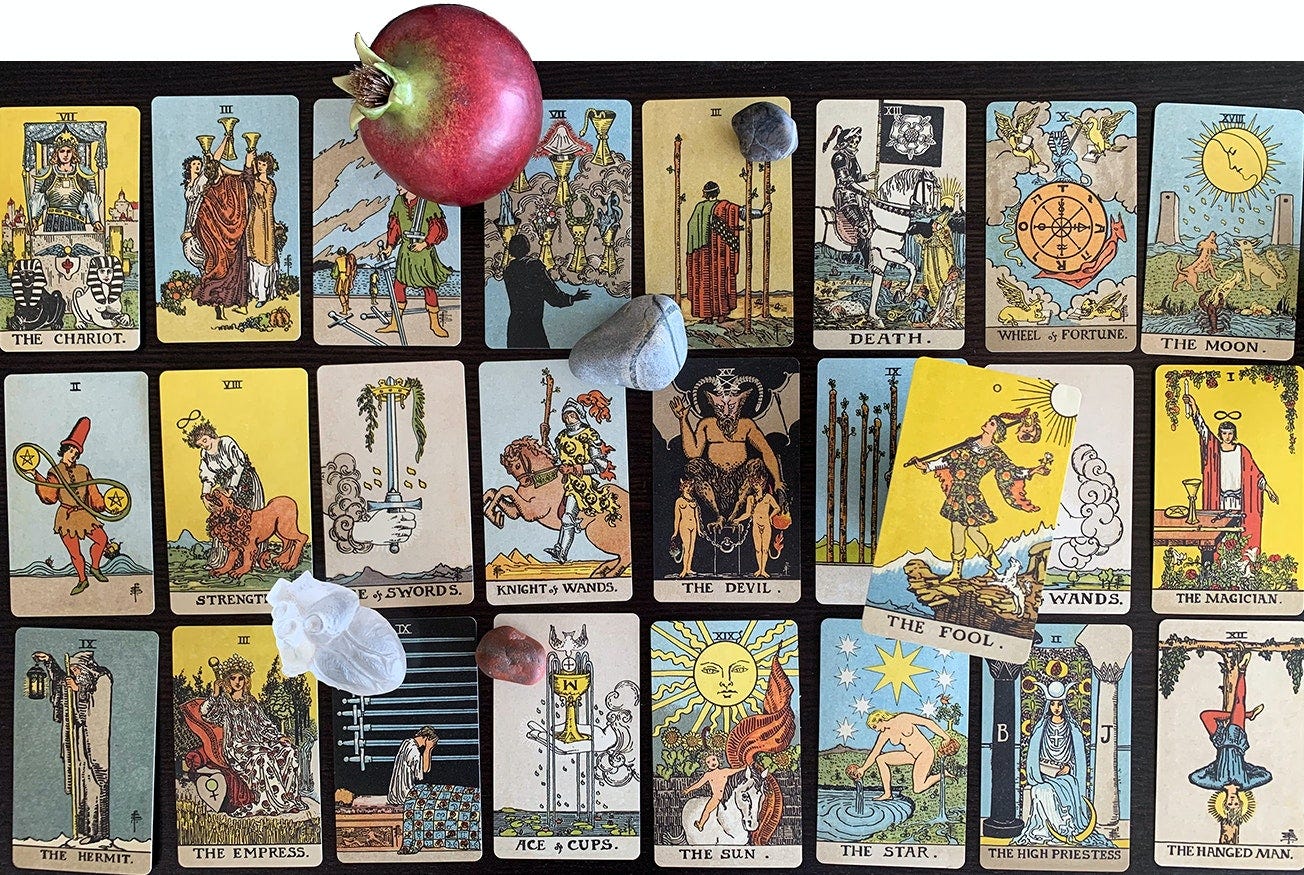

Try this sometime with your Waite-Smith deck: Lay out all of the cards, in no particular order, upright, and in straight lines. And then sit back and study the tableaux vivant before you. After a short while, you’ll be pulled into the rousing horizontal plotlines.

With each card arranged on its own ‘proscenium’—but with a scale and perspective that links it inextricably to its neighbors—you’re in a theater watching actors come and go from the various set pieces.

The effect is beguiling and deliberate on Colman’s part, influenced as she was by designing costumes and sets for the various theater companies she’d worked with over the years.

In one of the several excellent and detailed essays in Stuart Kaplan’s definitive book, Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story, Tarot scholar Mary Greer writes that Colman’s illustrations leave a “legacy of…unaffected childlike naturalness and harmony of expression.” She also details the various styles and influences that guided Colman Smith’s hand:

The Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck owes its classic look to a combination of 15th century High Gothic woodcut playing cards favoring strong black lines, the Symbolist/ Arts and Crafts amalgam of medieval, romantic and folk styles of decoration, as well as the Japoniste use of strong line with flat color and perspective and favoring a diagonal emphasis, which is seen mostly in the Minor Arcana. The Japanese influence found in Ukiyo-e woodcuts (collected by Pamela's father…) is epitomized in the West by the printmaking techniques of fin de siécle French posters.

The Smith-Waite deck echoes how life takes place not only on a stage but within stages. We love cinema, television, and theater for the same reason. Our life, ‘costumes’, possessions—our family of characters—Smith’s illustrations—especially of the pip cards (the Minor Arcana) reflect the events of our life back into the story-making role of our imagination. A full spectrum of emotions—both primitive and evolved—are welcomed. No plot is censored.

It’s easy to take Smith’s illustrations for granted. At first pass, they appear breezy and inviting. But walk the totality of their path, especially the 22 cards that comprise the Major Arcana (the main focus of Waite’s intention to remake the Tarot) and you encounter forces culled from the cauldron of ‘destiny in the making’.

And of course, Death is there too; to bring the curtain down—until the next reshuffling.

The first draw

The exact origin of the 22 symbols that comprise the Tarot’s Major Arcana? You might as well ask the always-silent High Priestess—no definitive answer exists.

There are scores of different historical interpretations but the most concise, that spoke to me directly—having worked with the cards now for over four decades—is found in Gertrude Moakley’s book The Tarot Cards—Painted by Bonifacio Bembo.

Moakley (1905-1998) was a New York City librarian who laid the foundation for all modern Tarot scholarship. Her tenacity was undaunted and her writings on the Tarot created a standard that was hard to match. Like Colman Smith, we have Moakley to thank for how the Tarot found a suitable spot in contemporary life.

Prior to Moakley’s work, little academic attention was ever paid to the Tarot. The cards seemed a novel part of European history; their origin story diluted with each new creation of a particular deck.

In short, Moakley’s thesis details how the images that comprise the Major Arcana were inspired by the costumed figures who participated in carnival parades.

Those figures were based on Francesco Petrarca’s I Trionfi—a 14th-century Italian poem that celebrates life’s principal themes—love, fame, death—a parade of allegorical experiences that remain constant despite the vicissitudes of time.

Defining the suits

My sense is that Waite left the deck’s Minor Aracana (the 40 suit cards with their respective court cards—56 in total) for Colman to interpret as she deemed best. Waite’s short and often contradictory divinatory meanings of the minor cards, in his Pictorial Key to the Tarot, seem perfunctory and sometimes a muddle.

If these were the descriptions that he offered Colman Smith to work from you can see why she broke free to follow inspirations germane to her history. Also, Colman Smith had a wealth of knowledge to cull from related to mystic Christianity and its symbols, several of which appear throughout the Minor Arcana.

In his detailed analysis of the creation and printing of the Waite-Smith deck, playing card historian K. Frank Jensen notes the existence of a 15th-century Tarot deck created by an unknown artist, a deck that might have influenced Waite and Colman Smith:

Shortly before Pamela Colman Smith was commissioned to illustrate the deck, the British Museum had received [in 1907] a set of photographs of the so-called Sola-Busca tarot deck as a gift from the Sola family, which for years had been kept close within the family. Waite, who frequented the British Museum regularly may have mentioned this set of photos to Pamela, in any case it is evident, that part of her inspiration for the minor arcana came from them. Several details in Pamela's images were reworkings of her own earlier paintings and drawings; art historian Dr. Melinda Boyd Parsons supports the idea that many of the tarot characters are portraits of Pamela's friends. For example, the actress Ellen Terry be seen as the Queen of Wands and in the Nine of Pentacles and Florence Fan (a prominent Golden Dawn member) portrayed in The World.

Although the Sola-Busca deck featured full illustrations of the suit cards, most of those depictions seem capricious—distanced from what Colman Smith devised for her final imprint on the Minor Arcana.

Some Tarot scholars have considered that Colman Smith devised a traceable narrative through each of the four suits. A love story that unfolds within the suit of Cups. A warrior tale within the suit of Swords. But I’m not convinced of this.

It wasn’t until I encountered Crowley’s The Book of Thoth that I finally understood how the suit and court cards were assigned specific meanings. Waite worked from the same source, Book T, published by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and allegedly written by S. L. MacGregor Mathers one of the order’s founders.

Robert Wang, co-creator of The Golden Dawn Tarot (yet another deck that worked with the same matrix as defined by the occult order), writes in his book The Qabalistic Tarot, “The Golden Dawn, Waite, and Crowley decks are agreed in their conceptual dependence on the principles of Book T, a set of Tarot papers issued to members of the inner lodge of the Order of the Golden Dawn. The principal suggestion of the papers is that the key to the Tarot is the Qabalah and the Tree of Life.”

Waite either shared this material with Colman Smith directly or reinterpreted it for her while overseeing his deck’s Major and Minor divisions, including the court cards.

Starting with the ace, each series in the suits depicts how the Breath of God passes down through the Four Worlds of the Qabalah. Commencing with the purely spiritual (at the ace) to the grossly material (the ‘ten’ card for each suit). If anything this would have been the ‘narrative’ flow that Colman Smith finessed.

With the wands and swords suit, this is particularly evident, where the cards numbered 8, 9, and 10 depict the gravity and burden of increased numbers. You can’t get any more flattened into the earth as Colman Smith’s take on the Ten of Swords, where the suit’s weaponry pierces a slain figure from head to toe.

If Waite was also inspired by the same system Crowley employed for the Lesser Arcana twenty years later—he doesn’t directly say. And as I’ll share in the second installment of this article Waite eventually moved away from his initial attempts to enshrine the Qabalah into his second ‘deck’ of cards.

Still, there is no clear-cut explanation as to how Colman Smith created what is essentially the most endearing component of any Tarot deck—the animated images that comprise the suit and court cards.

To date, the most specific research I’ve encountered is the essays included in the aforementioned Kaplan biography on Colman Smith. Should you wish to delve deeper into the mystery that’s your book.

Look but don’t look

Despite a 21-year gap between their ages, Waite’s partnering with Colman Smith was both rousing and fated. A relationship that would carry both of their purposes far into the future; imparting longevity of influence neither could have imagined.

Waite’s intentions were two-fold. First, create a Tarot that could be made available to English occultists. Those aspirants and teachers who wished to explore the esoteric secrets said to be inherent in the Tarot.

Prior to printing the Waite-Smith Tarot, individuals had to make their own deck or order one from abroad, mainly from France, where the occult interest (which reached England in the latter decades of the 19th Century), originated and where there was also a long tradition for playing Tarot as a game of chance.

The second was his desire to correct the popular misapprehensions that dogged the Tarot.

Inspired by Colman Smith’s mediumistic tendencies—the artist possessed an uncanny ability to ‘see’ music and then translate the sonics into her two-dimensional art—their creative efforts allowed Waite to run wild through the forest of symbols and emblems he loved to evoke for their mystical connotations.

As the author of his rectified Tarot, Waite struggled to preserve (withhold from the unwashed) the esoteric associations interwoven into his deck’s Major Arcana.

While attempting to write intelligently about what exactly the reader—and purchaser—held in her hands—he backpedaled to preserve the Tarot’s secrets; inner wisdom privy to the highest adepts of his mystery school.

Attempting to read his book, A Pictorial Key to the Tarot is a protracted lesson in double-binds. Waite would hint at revelations while dodging his intent with backstrokes that shrouded and occluded each step of the way.

As Tarot scholars Ronald Decker and Michael Dummett note in their superbly researched book The Occult History of the Tarot: “Waite had the egoist’s trick of insisting on both eating his cake and having it, while denying to others the right either to have or to eat theirs.”

In PART TWO of this essay (for paid subscribers to WOODRUFF) I explore the public’s enthusiastic reception of Waite’s Tarot and consider the synastry of A.E. Waite and Pamela Colman Smith’s horoscopes. In PART THREE I’ll take a detailed look at Waite’s second attempt to create what he hoped would be an unsullied representation of his occult visions of the Tarot.

Love,

Really enjoyed this! I'm about to publish a tarot stack myself

Excellent article. Loved the simple collages.