Gone Dude

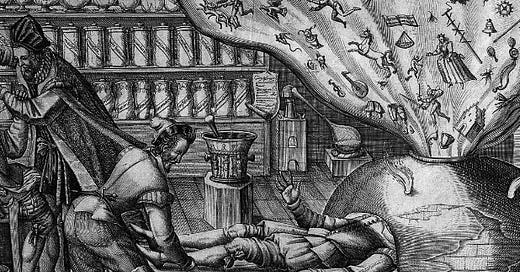

Why I abandoned hybrid spirituality and returned to James Hillman and his alchemical polytheism.

“Everything I’ve ever let go of has claw marks on it.” —David Foster Wallace

WHEN I DECAMPED FROM A twenty-five-year commitment to a spiritual school, I moved directly into the rogue psychologist James Hillman’s nowhere place. The shift to Hillman was in the spirit of the via negativa (essentially the study of what not to do.) The via negativa is similar to the Sanskrit term neti neti, which means “not this, not that.”

Hillman’s iconoclastic approach to the therapeutic model is a perfect fit for someone (me) who still feels a need for ongoing mystical discourse but only from within a model that self-destructs as soon as some thesis or revelation is conferred. The gist is that there is nowhere left for one’s mind to perch. Or as the Buddha put it: “Architect, you will not build your house here again.”

And as life is a permanent condition of unrelenting change, well, my approach made sense. Too, at this point, life was more and more leaning towards the shorter end of the stick. Adopting another idée fixe to anchor myself to was out of the question.

Hillman gave me enough wiggle room to still keep my mind entertained with different studies and ‘takes’—but as conveyed by someone who knew better because he himself was self-immolating right before his (and our) inner vision. Talk about a hardcore Aries.

Like a homing device, an instinct in my psyche understood that Hillman’s polytheist and pantheist1 constructs would be a good place to linger once I’d shaken off the conceptual vestiges from my school’s too-tight cocoon.

Hillman—especially in the latter years of his life—came to embody the spirit of Suzuki Roshi’s suggestion that “One should live their life like a very hot fire, so there is no trace left behind. Everything is burned to white ash.”

Hillman also valued and paid homage to Heraclitus’ scattered fragments and stingers like: “The name of the bow is life, but its work is death.”

Roshi’s red-hot words made sense to me in the way that 2 plus 2 equals 4 is a good fit. I don’t need to believe in the equation to value its completion. And completion—“life’s work”—as Heraclitus put it—has been more and more on my mind, especially after my mom’s death last year.

I was a free agent, but I also valued the power that accrues within a dialectic alembic. “Where two or more are gathered…” —that whole thing. And so I toyed with the notion of beginning a therapeutic relationship with a shrink. That might read as a circumlocution, but hang in here with me.

Memento Mori

Towards the mid-point of my time with the spiritual school, I realized I continued to remain in the school because I hadn’t come to terms, of my own discretion, with my death.

In fact, an ever-present binding element—sort of like a gimmick—within the school was that its various teachings, meditations, and practices were promoted as a means to an end when it came to one’s end—when the time arrived to wrap up one’s earthly ‘embodiment.’

Within the precepts of the school, this was achieved, tacitly at first, by espousing that life continued after death. This included hoary Theosophical-like descriptions of the soul sojourning onward after one’s demise, constantly evolving and ascending through states of boundless freedom.

Wow! Really?