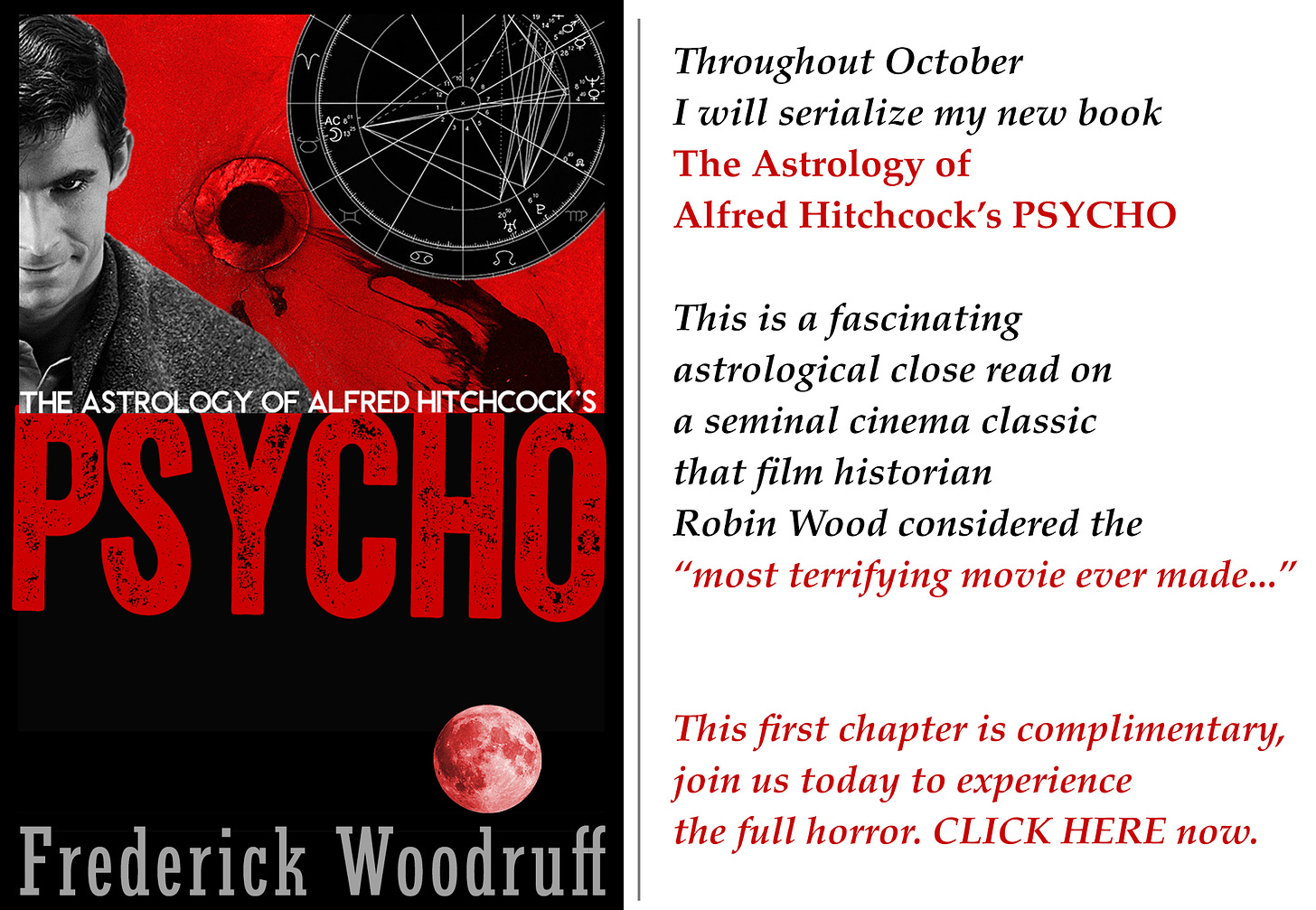

CHAPTER ONE: The Astrology of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho

Hitchcock unwittingly supplied astrologers with a horoscope for his horror classic. What does it reveal about the film's black heart?

“That we carry within us somewhere every human potentiality, for good or evil, so that we all share in a common guilt, may be intellectually, a truism; the greatness of Psycho lies in its ability, not merely to tell us this, but to make us experience it.” —Robin Wood, from Hitchcock’s Films Revisited

PSYCHO IS ALFRED HITCHCOCK’S MONA LISA.

And similar to Leonardo da Vinci’s premiere portrait—an icon that has devolved into a cliche—we no longer register Psycho’s allure and seminal power. The film is so much a part of popular culture we’ve bypassed its cunning artistry and black heart. Familiarity breeds amnesia.

Certainly, Psycho doesn’t compare to Hitchcock’s majestic classic North By Northwest. Nor his gorgeous study of necrophilic obsession, Vertigo—now considered the greatest film ever created (dethroning Citizen Kane from that accolade a decade ago).

Lazy associations (and endless pop cultural references) have revised Psycho into a cinematic relic, trivializing its subversive intelligence. Psychology 101 defines this as a defense mechanism. And this is understandable. To minimize and edit Psycho’s influence is to distance ourselves from the film’s savagery. Believing we have a grasp of Psycho is akin to whistling past the graveyard.

As the Canadian film scholar Robin Wood declared, Psycho is the most “terrifying motion picture ever made.” His appraisal sounds anachronistic when you consider the brash hype that touts modern-day horror films—most of inferior quality. But Wood was an astute critic, philosopher, and closet psychoanalyst. So, we are wise to honor his praise. (I’ll detail more on the importance of Wood in interpreting Hitchock’s work as we travel deeper into my book’s heart of darkness.)

Dangerous Landscapes and Horizons

When you imagine the world’s most famous painting, the Mona Lisa, your inner eye conjures the icon instantly. The woman’s face, her peculiar smile, and perhaps her resting hands dominate our memory. But what of the portrait’s primordial, lunar-like background with its ruddy ‘road to nowhere’? The mind blots this from recall. Why?

Camille Paglia points out that the landscape of the Mona Lisa is “deceptive and incoherent. The mismatched horizon lines, which one rarely notices at first, are subliminally disorienting. They are the unbalanced scales of an archetypal world without law or justice.”

In a similarly subliminal way, Psycho is designed to titillate and spook—Hitchcock called it a ‘fun picture’ and likened its aimless path to a fairground’s roller coaster. But his “Ah, shucks” stance was a PR bluff. A ploy that confirmed his dedication to mislead in a manner that would amplify the horror factor of his creation for those viewing the film for the first time.

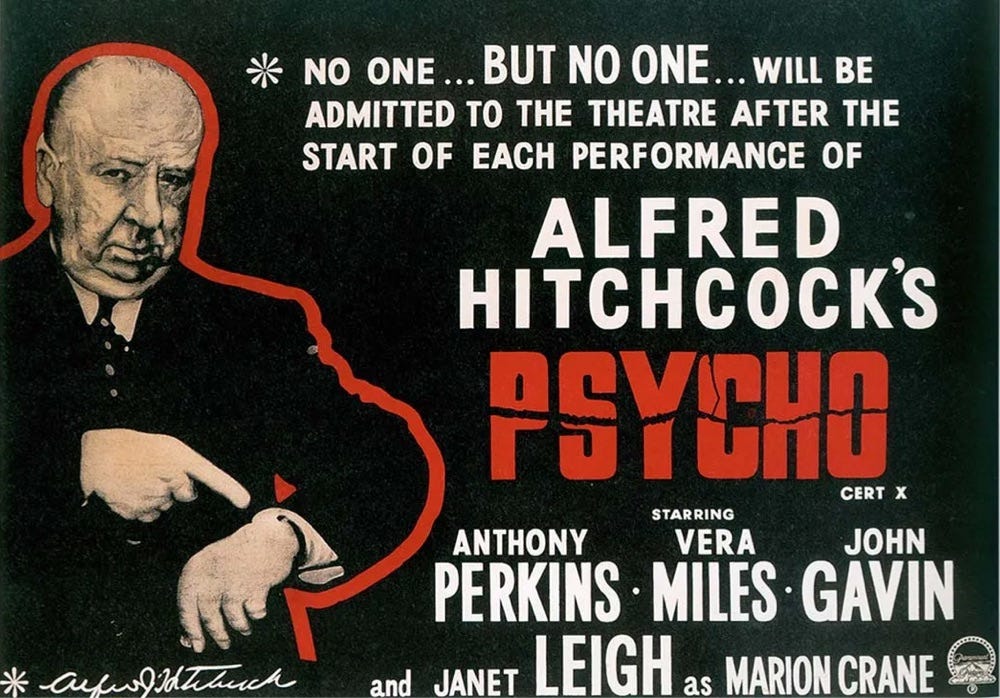

Remember, Hitchcock forbade individuals from entering the theater after Psycho’s first reel began to turn. A radical restriction when filmgoers in the early 60s drifted in and out of movies on a whim—entering, often during the middle of a film, and then staying to catch up with the plot’s opening scenes.

To rob the curious of the film’s shocking one-two-three punches, he also purchased, near and far, every copy of Robert Bloch’s book, Psycho, that inspired the film. This ensured moviegoers would not be deprived of their rightful dose of trauma.

On the surface, yes, Psycho is a 1960s carnival attraction. But the film’s conceptual framework, background, and heartbeat work as an incessant pulse that pokes and uproots unsavory impulses within our unconscious (alluded to in the opening quote from Wood.) Troubled psychic states that remain repressed but, once disturbed, begin to torment us.

These are the very anxieties that Hitchcock aimed to convert into haunting aftereffects—lingering moods and misgivings that would nag us after the film ended.

A Leonian Comand of Psychological Peculiarities

Hitchcock—a calculating Leo with his Moon conjunct Jupiter in Scorpio and Mercury in Virgo—controlled every frame of film he showed us. His astrological signatures equate to a masterful command (Sun) of material reality, coupled with a knack for psychological insight (Moon) and attention to minutia (Mercury). And this artful command is evident in all of his films, and especially so throughout Psycho.

The rhythm of the film’s tight editing mirrors the compressed perfection of a dream. Content is never wasted or haphazard in a dream. Contradiction and paradox blend seamlessly. And such is the airtight consolidation of Psycho’s method and manipulation of time and space. But like the deranged, craggy landscape that haunts the background of the Mona Lisa, Psycho‘s horizon line—the film’s trajectory—is a murky mind fuck.

Aside from its assault against cultural taboos (the motion picture was the first to feature a flushing toilet), Psycho undid the hallowed tradition of the Western dramatic arc. As Wood notes: “The film conveys a sense of endless journey leading nowhere…”

Tally the significant moments within Psycho. They are aimless: Murder has no moral or motive, the undead live and ‘converse’ with the living, repentance is punished by assassination, and the familiar familial hierarchy is turned inside out—made incestuous, a convoluted compounding that resulted in transvestism and psychosis.

Starting at the End

Even the film’s tagged-on ending—where a blustery psychiatrist explains ‘what it all meant,’ why Norman Bates did what he did—is a farce. The useless medical testimony tacitly implies that psychological insights offer no respite, no meaning.

As Psycho concludes, its unresolved miasma touches off our secret doubt that not much in life has ‘meaning.’ At least not in the way we tell ourselves. This existential problem haunts all of humankind and, over time, creates religious and philosophical structures to offer us solace. Hope. A road and direction to follow home to heaven. But as an old adage says, “Hope dies last for humans.”

But for a fixed sign dominant horoscope (Hitchcock’s Leo ascendant and Sun with his Scorpio Moon conjunct Jupiter), there’s always one more nail ready to be driven into the coffin. One more punch to thrust into our unconscious.

Most subversive films, especially in the 1960s, would close with, at minimum, a pittance of solace to the audience (moral censors back then almost always demanded this). But just as the viewer is readying to leave the theater, Hitchcock mischievously closes Psycho with a rapid-fire set of imaginal injections. Each is designed to deflate the psychiatrist’s explanations by yanking us back into the aftereffects of the horror.

After watching the closeup of Norman’s face morph into his mummified mother’s while sitting in the police department’s holding tank, Hitchcock insinuates a hurried five-second shot of the back end of Marion Crane’s car being uplifted from a mucky swamp.

Anyone familiar with dream analysis knows that a single image like this—the backend of a vehicle designed for forward motion—emerging from what looks to be a pool of shit, signals the start of a long, complex analysis, not its conclusion.

Hitchcock seems to be winking and saying to us: Goodnight … and good luck.

Love,

Next, in CHAPTER TWO, for my paid subscribers, we take a first pass at Psycho’s horoscope to identify key astrological signatures directly mirrored in the film. The Psycho chart is brutal, symbolizing the dark face of Mothers and the confused mindset of unhinging females in. And of the men in the movie? — poor dudes — all are locked away in the chart’s 8th house. Join us today!

The opening image design by FW for Nightcharm, Inc.,© 2023. Shower image via YouTube. Mona Lisa via Wikipedia, Car/swamp screencap via YouTube.

I want to invite you to subscribe to my new free newsletter, The Dahmer Diaries. I’m writing a novel about Jeffrey Dahmer, and my posts will detail the craft of fiction, the blending of True Crime and the imagination, and how astrology pulls it all together.

Something for the whole family!

Brilliant 👏

The dredging up of Marion's car in the very last second of 'Psycho' is the Return of the Repressed. Norman has retreated into his mother's personality: I didn't do this; Norman did this. But the Return of the Repressed suggests this hiding out in a second personality will soon burst. And Norman will be left, as in the iconic poster of Anthony Perkins, shrieking with one hand covering his mouth and the other hand flung out to push away the truth.