• ALBERT CAMUS OPENS HIS BOOK The Stranger with, “Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday.” This is profound because it is so ho-hum and jarring, but also it reveals a remarkable truth. The two sentences expose the incredulity around registering a death. An example: Shortly after I was told that my mom had died, the builders next door kept pounding away at the cinderblocks they were excavating. Death is extraordinarily ordinary. The world doesn’t pause like you imagine it will or should. Thus, “Mother died today. Or yesterday” could be, “Hey, hand me that hammer. Is Jerry picking up lunch?”

• Death is similar to birth in that during birth—once the cervix dilates, there is no stopping the baby’s arrival. A portal has appeared. And the reverse with death. The portal appears, and nothing can prevent its sucking action from taking us in the opposite direction. When your mother goes, you realize you’re next in line because you feel—palpably—the suck.

• Gurdjieff said a person never knows the feeling of being truly alone in life until their mother dies. No one anywhere will ever have a confidential interest in me or my doings like my mom. No one. And that’s fine, it’s nature’s way. Too, she earned that innate intimacy. I mean, I was forged in the cauldron of her body.

• Telling my mom I loved her over the phone several months ago while she was in the hospital—after I dictated the need for hospice and forced her to purchase a mortuary plan for cremation—(and assuming she’d disconnected the call when she hadn’t)—I overheard her say to the nurse: “That’s my oldest son. The German. The Gestapo.”

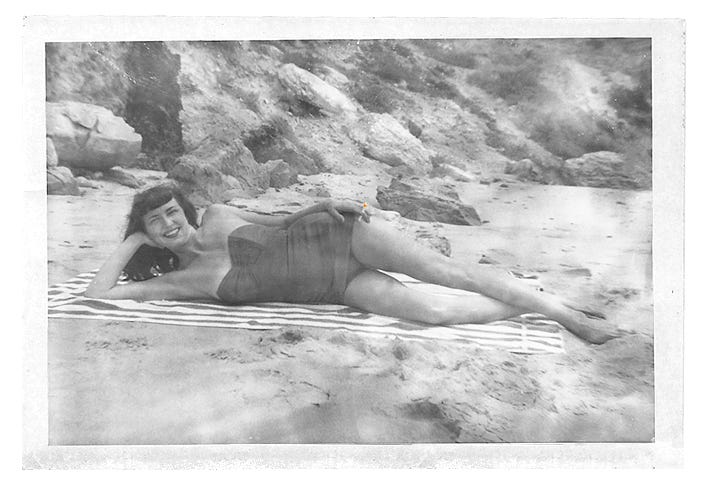

• Sagittarius Sun. Libra Moon. Libra rising. Venus, the chart’s ruler, in Scorpio. Always an edge of humor that leaned into the black. The legendary Sadge tactlessness—but with that sting of truth to push everything into the existential. Her overriding charm and physical beauty overwhelmed me as a kid. Parents are already larger-than-life totems in our lives, but when they possess physical beauty, a kind of weird glamor interferes with how the parent/child dynamic registers. You come to think that all life should be about beauty (and, as related to my mom: about truth-telling.)

• I’m 12 years old and decide it’s time for my mom to stop smoking. I order from Johnston and Johnston—a novelty shop that advertises in the comic books that I read—a bunch of tiny explosive charges that slide discreetly into a cigarette’s tip. These detonate randomly on my mom, depending on which cigarette was tampered with in the pack. I overhear her tell my grandmother one afternoon, “That crazy fucking kid is going to kill me.” But she doesn’t stop smoking until she flips her car on a rainy night on the freeway home from Hollywood, where she’d been out peddling her music. (She was a talented songwriter.) She snaps her spine and is saved by a male nurse who witnessed the catastrophe and pulled over to protect her and rally help. The crash finally ended both her smoking and drinking. My request and the explosives weren’t strong enough.

• Pulmonary disease was the malady that took her out—finally—50 years later.

• The night before her death, while she’s under hospice’s ‘comfort care,’ I’m amazed at how my consciousness turns uni-local. I’m watching TV on the couch when, in a flash, the division between inside and outside vanishes. There’s nothing more tedious than listening to someone describe their acid trip or moment of cosmic consciousness. But amidst my everywhere-nowhereness, I was also five years old and 90 years old. And recalled memories, I didn’t know I’d retained. Afterwards, this occurred to me: 45 years of continuous spiritual seeking—through schools, meditation, Jungian therapy, bodywork, sex and psychedelics—to hopefully register a more ‘authentic life.’ But in the end it’s the ‘death space’ that delivers my clearest, most certain insight. I’m recomposed by nature. (And my mom’s imminent liftoff.)

• I’m three years old, and my mom discovers me on the front porch moments after I’ve swallowed an entire bottle of syrupy sweet ant poison. Ambulance, stomach pumped, my mom gives me my life for a second time. Years later, I ask her what she and the paramedics talked about after the alarm subsided. And she tells me she told them, “This goddamned kid.”

• Right after I started to study astrology as a teenager, I asked her about my birth. She told me it had been dreadful. The staff had wheeled her to some shadowy corner in the hospital and left her there, amidst her contractions, while trying to direct the doctor to the correct floor. This was her first birthing experience. She was young and worried for her life. “The pain was a bitch,” she told me. All of this fitting Pluto (death) on my ascendant (the point of our origin).

• Insult to injury. When the nurses finally brought me back into the room for her to cradle, she burst into tears. “You were so ugly. You looked like an old man.” When I asked what she assumed I would look like, her double Libra side answered with: “Like the Gerber baby in all of those advertisements.”

• After my grandmother’s death and my younger brother’s death, my mom kept their ashes in a hallway cupboard for decades. Untouched. Unexamined. Very Sagittarius, “Don’t look back. Tomorrow’s a new day.” One April afternoon, she called to tell me she’d been on a spring cleaning bender, selling items, Goodwilling others with manic fervor. She eventually confessed to tossing the cremated remains into the kitchen garbage. “My God, mom, I can’t believe you did that.” Exasperated, she exclaimed, “Well, for chrissake, they aren’t there anymore! And I needed that shelf space.” I busted out laughing.

• Recently, I sent her an article on a particular subject I figured she'd be interested in. She responded via email—the entirety of which said: “Too much reading, what does it say?” Or on the phone several months ago, after a protracted pause. “Well, we might as well hang up—we’re just wasting time.”

• The poet William Stafford’s mom sounded like my mom. He wrote:

“My mother would say abrupt things, reckless things, liberating things. I remember her saying of some people in town, ‘They are so boring you get tired of them, even when they are not around.’”

• After her third day in hospice, which my brother and I euphemistically called ‘skilled care,’ she said, “Look, between you and me, I’m not ready to be put out to pasture.”

• What I’ll miss most? Calling my mom—I’m a Cancer, we spoke every day—and when her phone notified her that it was me, she’d answer straight away with, “Hi, kid!”

• Bye, Mom.

Love,

Opening image: My mom, Long Beach, California, mid-1940s, photograph by Reid Miles.

Twitter • Facebook • Instagram • Spotify • YouTube • Books • Consultations

You've so often written about your mom over the years, I felt like I knew her, too. You know, every now and then, I have the strongest urge to talk to my mom and feel bereft that she is not there; little death confrontations along the way to my own demise. Thank you for sharing such an intimate aspect of your life. Your love will not die and it, too, can be a comfort. Hugs to you!

My sincere condolences. I loved hearing about your conversations with your Mom that you shared over the years. You really brought her character to life. She is legendary. I love this tribute to her <3 Be everywhere and nowhere, exactly where she is. xx